The Three Dark Kings

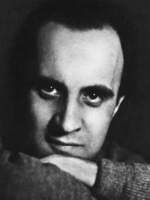

Wolfgang Borchert

Translated from the German by E. J. Campfield

He groped through the dark village. The houses stood disjointed against the heavens. There was no moon, and the pavement was shocked by the late footstep. Then he found an old wooden fence. He kicked at it with a foot until a board sighed rottenly and broke off. The wood smelled mellow and sweet. Through the dark village he groped his way back. There were no stars.

As he opened the door (it moaned, this door) the pale-blue eyes of his wife looked toward him. They looked out of a tired face. Her breath hung white in the room, it was so cold. He bent his bony knee to break the wood. The wood moaned. Then round about it smelled mellow and sweet. He held a piece of it under his nose. Smells almost like cake, he laughed softly. Don't, said the eyes of his wife, don't laugh. He's sleeping.

The husband laid the sweet mellow wood in the little metal stove. There it flared up and cast a handful of warm light across the room. This fell brightly upon a tiny round face and remained for a moment. The face was only an hour old, but already it had everything that belonged there: ears, nose, mouth and eyes. The eyes had to be big, you could see this even though they were closed. But the mouth was open, and it puffed softly. Nose and ears were red. He's alive, thought the mother. And the little face slept.

There are some rolled oats, said the husband. Yes, answered the wife, that's good. It's cold. The husband took more of the sweet soft wood. Now she's had her baby, and they will freeze, he thought. But there was no one to take revenge on for it. As he opened the stove door, again a handful of light fell over the sleeping face. The wife said softly: Look, like a halo, do you see? Halo! he thought, and there was no one to take revenge on.

Then there were people at the door. We saw the light, they said, from the window. We'd like to sit down for a few minutes. But we have a baby, the husband said to them. They said nothing more, but came into the room, breathed out fog and walked on their tip-toes. We're being very quiet, they whispered and walked on their tip-toes. Then the light fell on them.

There were three of them. In three old uniforms. One had a cardboard carton, one had a bag. And the third had no hands. Frozen, he said, and held up the stumps. Then the husband turned his coat pocket out. There was tobacco and thin paper in it. They rolled cigarettes. But the wife said: Don't, the baby.

Then the four stepped outside, and their cigarettes were four dots in the night. The one had thickly bound-up-feet. He took a piece of wood out of his bag. A donkey, he said, I've whittled on this for seven months. For the baby. He said that and gave it to the husband. What's wrong with your feet? asked the husband. It's dropsy, said the donkey carver, from hunger. And the other one, the third? asked the husband and handled the donkey in the dark. The third man trembled in his uniform. Oh, nothing, the first one whispered, it's only his nerves. He's just been afraid for too long. Then they stamped out their cigarettes and went back inside.

They walked on tip-toes and looked on the little sleeping face. The trembling one took two yellow bon-bons out of his cardboard carton and said: These are for your wife.

The wife's pale-blue eyes went wide as she watched the three dark men bend over her baby. She was afraid. But then the baby propped his legs against her breast and cried so robustly that the three dark men got up on tip-toes and skulked to the door. Here they nodded again, then they stepped up out into the night.

The husband looked after them. Some saints, those are! he said to his wife. He closed the door. Fine saints they are! He grumbled and fussed with the rolled oats. But there was no one to take revenge on.

The baby cried, whispered the wife, he cried so loud. Then they left. Just look, how lively he is, she said proudly. The face made a round mouth and cried.

Is he screaming? asked the husband.

No, I think he's laughing, answered the wife.

Almost like cake, said the husband and smelled of the wood, like cake. Very sweet.

Yes, and today is Christmas too, said the wife.

Yes, Christmas, he muttered. And from the stove a handful of light fell brightly upon the little sleeping face.

Translation copyright ©1974, 2002 by E. J. Campfield. All rights reserved.