A Small Contribution

On the Topic of RealismBertolt Brecht

Translated from the German by E. J. Campfield

Only seldom is it possible to test the actual effectiveness of artistic methods. Most often, one meets with, at the very best, agreement ("Yes, the way you have showed it is the way it is with us"), or that one has had an impact in some measure or another. What follows is a little test of a more fortunate sort.

With Slatan Dudow and Hanns Eisler, I produced a film called KuhleWampe which depicted the desperate condition of the unemployed in Berlin. It was a unified montage of relatively self-sufficient sequences. The first of these showed the suicide of a young man unable to find work. The censor took exception to this sequence, and the result was a meeting with the censor and the attorney for our firm.

The censor proved himself to be an intelligent man.

"No one denies you the right to portray suicide," he said. "Suicides happen. It is furthermore acceptable to show the suicide of a man out of work. This happens, too. I see no grounds for concealing any of that, gentlemen. I raise objection however to the manner in which you have depicted the suicide of your jobless man. It goes against the interest of the general public, which I am empowered to protect,. I am sorry gentlemen that here I must give you an artistic reprimand."

Eisler, Dudow and I sat silently insulted.

"Indeed, you will be surprised that I fault your depiction in that it does not seem human enough. All you have shown us is a man whom we can safely say is a stereotype. Your jobless man is not a real individual, not a flesh and blood man, unique from all other men, with particular sorrows and particular joys and, in the final analysis, with a particular destiny. His characterization is totally superficial, and you will excuse me as artists for stating strongly that we are told too little about him. His actions are merely used to make a political statement, which compels me to protest the film being approved. Your film tends to represent suicide as typical, not merely as the measure of one abnormally disposed character, but rather as the fate of an entire social class! You contend that society drives young men to suicide in that it denies them the opportunity to earn a living. And you certainly don't go to the trouble at all to point out moreover what the unemployed might be advised to do in order to bring about change. No, gentlemen, you have not behaved as artists, not here. No one would have been able to prevent you from showing the shocking destiny of one single individual, but that was not what you were concerned with."

We sat perplexed with the unpleasant feeling of having been seen through. Eisler wiped dejectedly at his glasses, Dudow writhed as if in pain. I stood and, despite my aversion to speeches, I gave one.

I relied strictly upon falsehood. I brought up certain characteristics that we had given our jobless young man, for instance that before hurling himself out the window to his death, he removed and put aside his wristwatch. I stressed that it was this pure human trait alone which had inspired the entire scene, and that we had indeed shown other people out of work who had not committed suicide -- 4000 of them filmed at a huge workers' Sports Rally. I defended myself against the outrageous accusation that we had not proceeded as artists and hinted at the possibility of a press campaign against such a claim. I did not hesitate to assert that my artistic reputation was at stake.

The censor showed no timidity about going into the particulars of the matter. Our attorneys were astonished to see that a proper and orderly debate on art was shaping up. The censor emphasized that we had given the suicide incident a decidedly demonstrative tone. He used the expression "a mechanical sort of thing." Dudow stood up and irritatedly demanded that we get the opinion of some psychiatrists. They would testify that actions of this type often bear a marked mechanical quality. The censor shook his head.

"That may be," he said stubbornly, "But you must after all concede that your suicide was hardly an impulsive action. The viewer doesn't at all want to stop it, as it were, which certainly would be the case with an artistic, warm-hearted human portrayal. Good god, the actor plays the scene as if he were demonstrating how to peel cucumbers!"

We had a rough time of it getting our film approved. As we left the meeting, we could not conceal our regard for this shrewd censor. He had penetrated far deeper into the essence of our artistic intentions than had our kindest critics. He had delivered a small seminar on realism. From the policeman's point of view.

Translation copyright ©1980, 2003 by E. J. Campfield. All rights reserved.

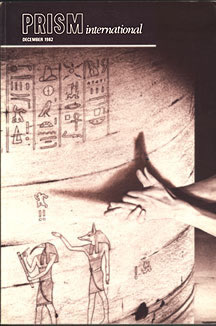

"A

Small Contribution on the

Topic of Realism"

appears here as originally published in

PRISM

INTERNATIONAL

Volume 21 · Number 2 · Winter 1982

The University of British Columbia

Vancouver, B.C.

...And

as presented in stage performances of

BRECHT

ON BRECHT at

The University of West Florida

University Theatre

Dr. Tom Long, Director

May 1980