My Pale Brother

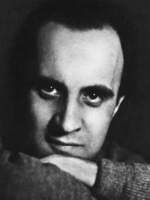

Wolfgang Borchert

Translated from the German by E. J. Campfield

Never before was anything so white as this snow. It was almost blue with whiteness. Aqua. So dreadfully white. The sun scarcely dared to be yellow in this snow. No Sunday morning had at any time ever been so clean as this one. Beyond in the background a dark-blue forest stood. But the snow was new and clean as a cat's eye. No snow at any time was ever so white as this one on this Sunday morning. No Sunday morning was at any time so clean. The world, this snowy Sunday world, laughed.

But of course there was one blot on it. It was a man in uniform lying prone and curled up in the snow. A bundle of rags. A ragged bundle of meat and bones and leather and cloth. Splattered dark-red with drying blood. The most lifeless hair, unpretensiously lifeless. All curled up, his last scream screamed, bellowed or maybe pleaded into the snow: A soldier. A blot on the never-before-seen snow-whiteness of the cleanest of all Sunday mornings.

Impressive portrait of war, rich in hue, enticing subject for water colors: Blood and snow and sun. Cold cold snow with warm damp blood on it. And everywhere the dear sun. Our dear sun. All the children all the world over say: the dear dear sun. And it shines upon a corpse that screams the unheard scream of all the dead puppets: The silent dreadful silent scream! Who among us, stand up, pale brother, oh, who among us can stand the silent scream of the puppets, when, torn off their strings, so stupidly distorted, they lie sprawled around on the stage. Who, oh, who among us can stand the silent scream of the dead. Only the snow can stand it, the iciness. And the sun. Our dear sun. Over the torn-away puppet stood one who was still whole. Still working. Over the dead soldier stood a living one. On this clean Sunday morning in never-before-seen white snow the standing one held this following dreadful unspoken conversation with the fallen one:

Yes. Yes yes. Yes yes yes. Now your poking fun at things is over with, my dear fellow. Your endless poking fun. Now you've got absolutely nothing more to say, heh? You sure aren't laughing anymore, heh? If only your women knew how pathetic you look now, my dear fellow. You look so pathetic now that you're not poking fun at things anymore. And in that stupid posture. Why have you got your legs pulled up against your belly so horribly? Oh I see, you took one in the guts, huh? So you're all smeared with blood, huh? Looks so unappetizing, my dear fellow. Did you splatter your whole uniform with it. Looks like black ink splotches. It's a good thing your women can't see that. You always made such a fuss about your uniform. Everything had to fit at the waist. When you made corporal, you paraded around in those low-cut polished boots of yours. And they got polished for hours if you were going to the city in the evening. But now you won't be going to the city anymore. Your women will enjoy the advances of other men now. Because now you're not going anywhere at all, you get it? Not anymore, my dear fellow. Never never more. And you won't be laughing anymore with your endless poking fun at things. Now you lie there like you can't even count to three. And you can't. That's a tough break, my dear fellow, very tough. But it's good this way, very good this way. Because you will never say to me again "my pale brother droopy eye." Not ever again, my dear fellow. Not from now on. Not you. And the others will never cheer you for it again. The others will never laugh at me again when you call me "my pale brother droopy eye." That means a lot, you know? That means a whole lot to me, I can sure tell you that. They used to torment me about it in school. They surrounded me like lice. Just because my eye had that little defect, because the lid hung down like this. And because my skin is so white. So pasty. Our pale little boy always looks so tired, they always use to say. And the girls always asked if I was about to fall asleep. Because my one eye was already half closed. Drowsy, they said, you said, you all thought I looked drowsy. Well I'd just like to know which of us two is the drowsy looking one now. You or me, which one? You or me? Who is "my pale brother droopy eye" now? Which one of us? Who is it, my dear fellow, you or me? Me, maybe?

As he closed the pillbox bunker door behind him, a dozen gray faces came out of the corners toward him. One belonged to his sergeant. Did you find him, lieutenant? asked the gray face and it was dreadfully gray.

Yes. Near the forest. Gut-shot. Should we bring him back?

Yes. Near the forest. Yes, naturally. He must be brought back. Near the forest.

The dozen gray faces disappeared. The lieutenant sat on the metal stove and picked the lice off himself. Just like yesterday. Yesterday he had been picking the lice off himself. Because someone had to go up to batallion. The best of them, he himself, the lieutenant. As he was picking up his shirt to put it back on, he had listened. Shooting broke out. There had never been such shooting before. And as the messenger tore open the bunker door, he saw the night. Never before had a night been so black, he realized. And then there was Sergeant Heller, the one who sang. Who told in turn of all his women. And this Heller in his endless poking fun at things had said: Lieutenant, I wouldn't go up to batallion looking like that. I'd requisition double rations first. Someone could play your ribs like a xylophone. You really look pathetic. Heller said that. And in the darkness the others were certainly all grinning. But someone had to go up to batallion. So he had said: Fine, Heller, let's give your poking fun at things a chance to cool off a bit. And Heller said: Sure. That was all. No one said anything else. Simply: Sure. And then Heller was gone. And then Heller did not come back.

The lieutenant pulled his shirt on over his head. He listened as they returned. The others. With Heller. He will never again say to me "my pale brother droopy eye," whispered the lieutenant. From now on he will never say that to me anymore.

He got a louse between his thumb nails. There was a crunch. The louse was dead. On his forehead -- he had a little splatter of blood.

Translation copyright ©1974, 2002 by E. J. Campfield. All rights reserved.